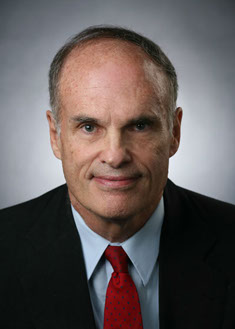

James W. Wimberly, Jr.

Senior Principal

Greater Atlanta Area

Featured Speaker

Experienced practitioners share their insights on the latest developments at the NLRB and what merit shop contractors should expect from the board in the second half of 2021, with a particular focus on the pro-labor agenda of the new NLRB general counsel.

James W. Wimberly, Jr., an AV rated attorney, is a founding principal of the firm and of the Wimberly Lawson Network. In over 40 years as an attorney, in private practice and early on with the US Department of Labor, and as a Professor of Labor Law, he has built a national reputation for excellence in comprehensively addressing the needs of employers.

Chosen by Best Lawyers in America every year since 1987 as one of the very top lawyers in labor and employment law, Jim is perhaps most sought after for his work representing employers in traditional labor management defense. He provides solutions to clients with respect to concerns such as union avoidance and union organizing and election campaigns, collective bargaining, plant closings, and, when it cannot be avoided, arbitration and litigation before the NLRB, EEOC, and all state and federal courts. Jim’s litigation experience is demonstrated by the litigation of two Title VII class actions that worked all the way to the U.S Supreme Court. As a preeminent expert in the area he has testified before the U.S. Congress.

Jim advises clients on how to best avoid labor concerns by analyzing industry trends, developing workable plans for regulatory compliance, training executives and management on workplace administration, and developing and implementing effective human resources standards and practices. In addition to employers he counsels national trade associations in the lumber, furniture, apparel and farming, and food processing industries, and state trade associations in the poultry and trucking industries.

Jim’s labor representation has led him to success on behalf of employers in hundreds of labor arbitrations. He has represented employers in over 50 union recognitional elections, has negotiated successful collective bargaining agreements involving thousands of workers in myriad industries, and has created strategies to terminate local, regional and nationwide strikes.

Notable successes include:

-

Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) Arbitrations: Resolved disputes respecting MARTA’s labor contract with over 3,000 employees through four interest arbitration cases and related collective bargaining.

-

National trucking company: Ended nationwide strikes affecting over 3,000 transportation workers.

-

Fortune 500 manufacturer of construction products: Performed labor and employment due diligence reviews in multiple acquisitions and developed revised organizational structure for the company following the acquisitions.

-

Fidelity Interior Construction Company v. Southeastern Carpenters Regional Council, 675 F.3d 1250 (11th Cir. 2012). The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a $1.7 million jury verdict against the Carpenters’ union. The jury found that the union violated Federal secondary boycott law by conducting an illegal “area standards” campaign which included bannering, picketing and handbilling at buildings where Fidelity was, had or might be working to coerce third parties into not doing business with Fidelity.

The author of Georgia Employment Law, Jim also regularly writes and speaks on labor and employment law issues. He served on the Advisory Board of Simon and Schuster's Business Practice newsletters, and formerly served on the Advisory Board to Commerce Clearing House's labor relations publications, and is a former member of the Board of Directors of the Georgia Chamber of Commerce. He is a co-author, along with senior principals Marty Steckel and Les Schneider on the book entitled Construction Industry Labor & Employment Law.

Education

Jim received his B.B.A. cum laude and his J.D. from The University of Georgia. He earned his LL.M. from Harvard University and did graduate work in labor relations at Georgetown University

James W. Wimberly, Jr.'s Latest Resources

Top 10 Most Important Labor and Employment Law Changes in 2025

As we normally do, we're planning a yearly review of 2025's labor and employment law changes, Friday, January 9th, 2026. Join the noon webinar with Jim Wimberly and Les Schneider to discover the “most critical subjects” for the year.