It seems to be a trend not only in the U.S., but around the world, for there to be a flurry of protests and walk-outs. Strike activity in the U.S., for example, is at the highest level in several years, after many years of extremely low levels of such activities. But now we seem to have a similar trend in often spontaneous walk-outs in even non-union plants in the U.S.

First, a brief review of the legal rules. A concerted walk-out, even in a non-union facility, is a protected, concerted activity. Therefore, employees may not be terminated or even disciplined for engaging in such activities. There are three exceptions, however, in special circumstances.

For example, non-union workers, like other workers, cannot engage in what the law calls an "intermittent" strike. There is a general principle that workers must either work or strike, they cannot combine the two. Thus, continuation of the same type of walk-out activity on repeated occasions or working partial days would violate this rule, and be what is called an "unprotected" activity subject to discipline or even discharge. On the other hand, there can be separate strikes or walk-outs over different issues.

The second exception is that workers may not conduct an illegal "sit-in" inside the employer's facility, which is in essence a trespass on the employer's property. Nevertheless, Labor Board rulings allow employees at least a brief opportunity to express their concerns to their employer, and require the employer to give plenty of advance warnings that it will consider a prolonged sit-in to be an illegal violation of the employer's property rights. Obviously, the advice of counsel both in the case of an "intermittent" strike and a "sit-in" are necessary.

Of course, employers can fall back on the general principle that while strikers or those walking out cannot be discharged or discriminated against, they can be permanently replaced. This means that the employer has the right to engage other workers to perform the work of those who are walking out, so that such replacement workers hired on a "permanent" basis need not be "bumped" when those striking or walking out seek to return to their former positions.

There are severe limitations, however, on the employer in the case of a permanent replacement of strikers. First, when a striker or person walking out seeks to return to work, that person, as a general rule, is entitled to fill a position that is vacant for which the striker is qualified. This means that while a striker or person walking out, who is in essence a striker, cannot "bump" a permanent replacement, but the striker has a right to a vacancy in the plant for which he or she is qualified. There are further limitations on the employer's rights in an "unfair labor practice strike" or walk-out, where employees walk out or strike to protest an employer's unfair labor practices. In this situation, once employees seek to return to work, they are, in fact, entitled to "bump" permanent replacements to their jobs hired after the beginning of the protest of the unfair labor practices.

Strategy in Dealing With Walk-Outs

The first strategy is probably to closely evaluate the walk-outs and/or threats of walk-outs to determine how serious and widespread they are. Overreaction to such walk-outs or threats of walk-outs may be counter-productive. On the other hand, not taking them seriously can also be dangerous, particularly where the employer can be severely hurt by such walk-outs and does not have alternative sources of filling the jobs or production.

Good planning and effective responses require some knowledge of the facts, such as how widespread the concerns are, whether they are serious, and what, if anything, can or should be done to address the situation. As part of this analysis, wise employers will consider what the real issues are, who is best to address the issues, either within or outside the company, and what the next steps should be.

To make these decisions, or to gather information, informal surveys can be taken on a one-on-one basis among "opinion leaders" in the facility, or in some cases "listening sessions" can be held with small groups of workers. Many employers have a history of having an effective internal spokesperson that can conduct such sessions with a high degree of credibility, and respond in a manner that is helpful to explain and/or address the concerns. If such sessions are used, the employer must consider whether to conduct such sessions only in the area generating the unrest, or other areas of the facility as well.

Punitive

The general approach addressing the concerns might be classified as punitive, feeling out, explanatory or conciliatory. Let us review each approach.

A punitive approach would be to "threaten" indignant workers with harm to the company as a whole because of their actions, pointing out why the contemplated walk-outs are not the way to address problems. Information might be communicated about the employer's right to permanently replace such persons walking out, and as long as the careful term "permanent replacement" is used, there is normally no need to go into any detail about the reinstatement rights of strikers if they seek reinstatement. Similarly, explanations can be given of loss of company pay, or sometimes loss of certain company benefits, or potential loss of similar benefits such as unemployment compensation as strikers normally do not get unemployment compensation (although there are exceptions in some states).

The previous approach has often been used in the past, but today's employment environment has changed the picture, and some companies have concluded that the punitive approach is not effective.

Feeling Out

In contrast, the "feeling out" approach is relatively low risk and offers many benefits. Sometimes workers simply want to voice their concerns and feel somewhat relieved in doing so, when someone listens to their concerns. Sometimes explanations can be given that are logical and understandable to the workers, and the explanation may ease their concerns or otherwise lead them to believe that requested changes are not practical. Finally, these listening sessions allow the employer to gauge the intensity of the controversy, thus enabling the employer to respond in an appropriate manner.

Explanatory

The third approach listed above is "explanatory." This means the company goes to great lengths to explain its situation, as workers may not be aware of the many logical reasons why a company can or cannot do something. This approach is also relatively low risk, but it may not be successful in all cases. Further, some importance should be given to how the company communicates this explanation, not only in the choice of words but the particular speaker or manner of communication utilized. For example, should the message be communicated by supervisors, HR, or even higher levels, and should it be communicated in writing and, if so, how. The options here are numerous, including having supervisors make brief statements, referring employees to a notice or poster on a bulletin board for more information, or providing handouts or attachments to paychecks, letters to home, etc.

Conciliatory

The fourth approach mentioned above is "conciliatory." This approach means the company not only listens to concerns expressed formally or informally, but takes some action in response to those concerns of a positive nature. Sometimes employees' concerns are problems that the company can actually correct and improve their business as well. Other times seemingly extra costs are incurred but can be ameliorated by more efficiency in a resolution. Sometimes the conciliatory steps do bring about extra costs to the company, such as granting improvements in pay or benefits in a manner that raises the company's labor costs. In evaluating the costs of such improvements, companies must consider the additional costs that could occur from further walk-outs and/or from employees going to a labor union for backing, resulting in a costly and divisive union organizing campaign.

This latter approach creates the old story of "feeding the hungry bear." Many years ago, it was considered extremely dangerous to reward employees for concerted activity by providing them some type of benefit. Just as a hungry bear comes back for more food and learns the techniques in doing so, employees may learn that walk-outs or threatening to walk-out is the way to bring better pay, benefits, or other improvements.

While the above concept of feeding the hungry bear remains a concern, in today's environment it often should not determine the employer's strategy. Being responsive to employee concerns is often not a negative generally of employer/employee relationships and may be a lesser cost in the long run than creating a bigger problem of further walk-outs and/or union campaigns.

In Conclusion

This analysis is more of a checklist of considerations in dealing with these issues. Unfortunately, every situation is different and requires different strategies. Also, because of the uncertainty in the correct approach, many employers may sometimes choose to simply sit back and see what happens before taking a major step.

Related Content

Get Email Updates

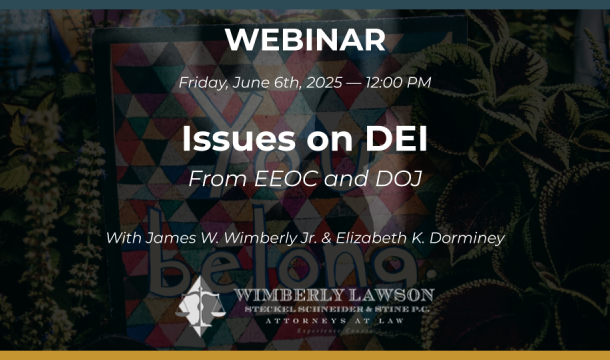

The EEOC and DOJ Issue Guidance on DEI

Considerations When Government Officials Show Up and Request to Meet with Individual Employees

How Jurors Evaluate the Fairness of an Employer’s Actions

Some of the Controversial Issues Currently Being Faced by Employers in Light of Recent Developments

Frequently Asked Questions About Recent Immigration-Related Actions